You do not need to leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait, be quiet, still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet. --FRANZ KAFKA

Friday, April 28, 2006

THE STORY OF TWO WRITERS

Soon after, I would linger beneath the covers with books like Little Women, Anne of Green Gables, and The Secret Garden, but I first experienced the deep communion between reader and fictional character with the famous girl detective.

In concept, Nancy Drew was created by a millionaire book packager named Edward Stratemeyer, who paid a young journalist $125 a book for volumes 1 - 7. Eventually the price escalated to a whopping $500. But a strange thing happened between the concept and the final product: the writer created a real character, a spunky young heroine who triumphed over the dangers and the complexities of modern life with flair and intelligence. In doing so, she spoke to millions of girls as they prepared to navigate the most mysterious world of all: adolescence.

I guess there wasn't so much curiosity about authors at that time; I never wondered much about Carolyn Keene. Nor were her age, her photograph, or the size of her advances used to trump up sales. The packaging of Stratemeyer's series was limited to the books. It did not extend to the author.

Meanwhile, Mildred Wirt Benson, the woman who brought Nancy to life for $125 and wrote all the best books in the series, quietly went about her life--and kept typing. When she was finally recognized at age of eighty-five, Benson was revealed to be a person much like Nancy herself: a determined optimist who learned to fly a plane in her sixties, and would continue to write for Toledo Times until her death at ninety-six. She left behind more than 130 novels--most written under pseudonyms and for a fee. Benson harbored no illusions that her novels would endure for the ages; and when she was finally identified, she found the adulation of her fans a mixed blessing.

Kaavya Viswanathan, who has grown notorious for the plagiarized passages in her novel How Opal Mehta Got Kissed...in the past week, seems to have struck a different kind of deal with her book packagers. It wasn't so much her writing skills they were after; it was her persona. Her status as a teen prodigy and student at Harvard was skillfully hyped to create buzz around the novel.

Until this week, Viswanathan seemed like the luckiest of writers. At seventeen, without ever agonizing over a single query letter or even needing to complete her novel, she secured a top notch agent and a half-million dollar publishing deal. Legions of talented writers who've spent years of their lives and a fortune in postage trying to attract the attention of the publishing industry, could only shake their heads in bemused frustration--or bitter envy.

Now everything has come into question-- from the the the exact nature of Viswanathan's authorship to the size of her advance. But the greatest question of all concerns the capricious nature of luck. Kaavya Viswananathan's novel may be reissued; and driven by its notoriety, it may sell even better than predicted. But it now seems that the grossly underpaid Mildred Wirt Benson, who spent most of her life in anonymity, may have gotten the better deal.

Thursday, April 27, 2006

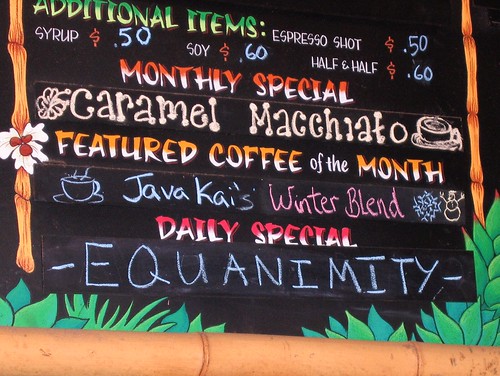

13 THOUGHTS ON EQUANIMITY

1. Equanimity doesn't know the difference between good news and bad news. They both have the potential to disrupt balance.

2. The past weeks have been full of exciting developments; there's been much to toast and celebrate. I've been happy, thrilled one day--and then the next day moody and petulant. Why? I’m getting what I want, right? Ah, the mysteries of Equanimity...

2. As yogis and dancers know, equanimity begins in the physical. Is it possible to have cerebral or emotional balance without first developing the physical side?

3. Equanimity is a "light" virtue. Wear it too heavily, push too hard to attain it, and you lose it.

4. In yoga, when practicing the tree, you focus on one point in front of you to keep your equilibrium. It works in life situations as well.

5. I need to be a tree more often.

6. Sometimes I think about what I'm going to say while other people are talking. That disrupts the equanimity of speech, the rightful balance between listening and speaking.

7. After two weeks of concerted effort, I got a little better at this. In return, I not only heard more, I felt more, I experienced more compassion.

7. Sometimes I sit at my desk too much. I forget to clean the house. I forget to go to the grocery store, or weed the garden, or walk down the street in the sunlight. Not good for equanimity.

8. I now have a kitchen timer next to my

computer. If I sit and write, write and sit too long, it goes off: bzzzz! Time to get up and see the day!

9. I waitressed a shift this week. It reminded me of the lessons in equanimity I've learned through my long career. There is the balance needed to hold a tray, to keep the pace of a meal flowing smoothly, but also the balance between serving, and accepting and respecting the service of others.

10. Some of the people I was waiting on didn't care about equanimity. They wanted what they wanted--now!

11. I mentally promised myself that I would never be one of those people who see what they want so vividly that they stop seeing anything else.

12. Drinking wine, as pleasant as it might be, is not always conducive to equanimity. Every few months I seem to be reminded of this again.

13. I found this quote from the little book Benedict's Way, which seems to describe true equanimity:

"No matter what kind of ruins you stand in, keep moving, keep doing what you must do, keep showing up every day."

Next week: My bugaboo--and Ben's: Order

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

THE PAPER CLOSET: A short true story

...whoever remembers their childhood best

is the winner,

if there are any winners.

--Yehuda Amichai (from 1924)

If Amichai is right, it seems like I'm NOT a winner. The six years I spent in elementary school, for instance, have eclipsed into a few brief scenes and some sharp memories of physical objects: the old paper cutter that looked like it might easily lop off a finger if you weren't careful, the crank pencil sharpener we needed permission to use, the hooks where we hung our coats in the hallway.

The school I attended was a fortress- like building in an old mill town. It has since been converted to an office building. Surrounding it was not the sprawling state of the art playground equipment and well-tended ball fields contemporary schools have, but a scrappy dirt yard. It was the place where I first grappled with the accumulated knowledge of the human race, where I formed passionate childhood friendships, and learned the secret rules and hierarchies that govern any closed society. But I retain only three truly vivid memories. I will share one.

It concerns my third grade teacher. Mrs. M.was perhaps the truly dolorous human beings I've ever encountered. Everything about her suggested a great heaviness. From the oppressive flatness with which she read a poem or recited the time tables to the underwater slowness that characterized her movements, Mrs. M. oozed gloom. Even her shoes were black and heavy.

On the day of my vivid memory, I needed permission to go to the girl's room. However, Mrs. M. was busy in the paper closet. Another anachronism, the paper closet was a pantry sized space where fragrant paper in various shapes,weights, and colors was stored in neat stacks on the shelves. Until that day, it was one of my favorite places. I squirmed in my seat while Mrs. M. remained in the closet with the door closed.

Only the threat of her morose countenance kept us quiet in our seats.

Finally, unable to wait any longer, I burst into the closet. There I came face to face with my teacher just as she was bringing a small bottle to her lips. Though I was not a very sophisticated child, I immediately understood what I had seen; and worse, Mrs. M. knew that I had. Her face deepened to an even more threatening shade of purple.

It can't have been more than a few seconds that we stood there trapped in the confines of that small space and our own awkward knowing. But illustrating one of the great mysteries of time, those few seconds have stretched into years. I took in every broken capillary on her mottled cheeks; I absorbed the deep misery in her green eyes. In that moment in the paper closet, I had inadvertently crossed the border between the semi-protected world of childhood into the wild geography of adult rage and pain.

"Get out!" Mrs. M. cried in her throaty voice, with a wave of her hand. "You heard me; go!"

"The girl's room...I have to go to the girls' room," I stammered, trying to restore the classroom to a place of predictable rules where I never had to contemplate Mrs. M's life as anything other than a teacher. Trying to take back what I had seen.

"Just go!" Mrs. M. repeated with a savagery that finally broke through her heaviness.

I ran all the way to the girls' room, ignoring the rules about walking in the hallway, and traveling only with the requisite permission slip in hand.

I lingered in the stall long beyond the acceptable time, but when I returned Mrs. M. said nothing. Somehow I had known she wouldn't. Instead, she turned her back and faced the black board, never to look deeply at me again.

I, too, would spend the rest of the year avoiding the dark emotions that colored her skin and filled her eyes.

As an adult, of course, I look on the woman in the paper closet with sorrow--and with empathy. I've never been trapped by the need for a furtive sip, but I have lived long enough to know my own variations of her anguish. I wonder if she feared I would tell someone. If she perhaps, worried for her job. Somehow I don't think so. Somehow, I think that as we confronted each other in the paper closet, she, looked at me deeply, too; and what she saw was the soul of a fascinated observer. One who would store the memory up and turn it over in her mind until she could understand it.

If she'd known what I did--even then--she would have also seen that someday, somewhere, I would write about it.

Wednesday, April 12, 2006

13 THOUGHTS ON COURAGE

In my admittedly half-hearted, but better-than-nothing attempt to imitate Ben Franklin and work on one virtue a week, I've dedicated the last seven days to courage.

This is what I learned:

1. I feel least courageous when I wake up in the middle of the night or after a nap. The world feels shadowy and unpredictable and treacherous at times like that.

2. Maybe I should take less naps.

3. I feel most courageous during the bright hours of the day when I'm actively doing something. Working. Walking. Singing along with Woody Guthrie or Aretha Franklin.

4. Maybe I should spend less time thinking and more time doing. And I DEFINITELY need more music in my life.

5. I am not called upon to save lives in my ordinary days. Courage for me is in little things: speaking up and saying what I really think, making the phone call I've been putting off, tackling an intimidating chore.

6. Courage sounds very lofty, but often it's a fool's virtue--not being afraid to be one, that is.

7. Most of our fears are based on a crazy misperception. We think we're immortal! If we were, every loss, every mistake WOULD be as monumental as we think it is.

8. A few times this week, I got a chance to share that good news with a frightened friend or family member: Whatever you're upset about, don't worry; it's temporary. YOU'RE temporary. I am too! Yippee!

9. Mostly, it helped; sometimes people just thought I was more crazy than they already believed. But because I was being foolishly courageous, I said it anyway.

10. Writing's temporary, too, though sometimes I start thinking that it's big and permanent and important; and then it saps my courage.

11. I refuse to be afraid of anything as small and antlike as words scuttling across a computer screen! I absolutely refuse.

12. Most days when I wake up, I lie in bed and think about things for a while. Sometimes I write a poem in my mind, but mostly, I just run a lot of petty things

and shadow thoughts through my head. It would be more courageous to jump up and face the day.

13. Tomorrow I will jump.

Next week: Equanimity

Sunday, April 09, 2006

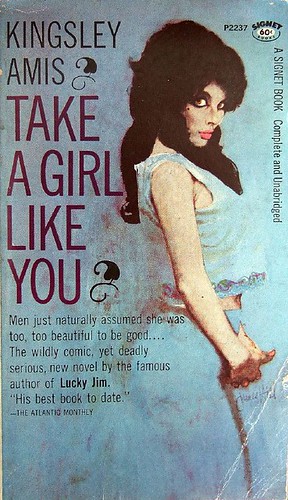

ON WRITERS AND AMBITION

On the back page of yesterday's New York Times Book Review, Joseph Finder brings a refreshing candor to the dirty little subject of ambition. Serious writers, it seems, aren't supposed to have any. They labor for art alone; they write "for themselves," eschewing even the desire for an audience. And if they have any hope of making--err, excuse me for uttering the word, money, well they've obviously not attained the necessary purity. Maybe five or ten more years of fasting on contributor's copies and Ramen noodles will do the trick.

In fact, Finder points out, the true literary scribe is so averse to the crass desire for success that ambition has even been banished as a fictional subject in contemporary literature. Today's ambition free novelists struggle with sex, with the legacy of defective parents, with the endless struggles of the Self; but the yearning for power or worldly recognition as a plot device is as dead as the ill-fated striver in Sister Carrie.

Sorry, but I don't buy it. Maybe my experience is different. Maybe it's just that I don't know any editors or professors of Creative Writing or until recently, even any other writers, who might have helped me network my way to publication. But in my experience, achieving publication in even a literary magazine with a print run of 500, is damn hard work.

Without ambition, would anyone spend a fortune in postage and time putting together dozens--or even hundreds--of packets of prose or poetry and complete with a carefully worded cover letter and an SASE. Would they endure the dozens--or hundreds-- of anonymous rejections--for every publication in a "good" journal? Would they take out loans it might take years to repay to cover the cost of an MFA program?

Like most writers, I write because I'm mysteriously impelled to do so and have been since childhood. If I was never published anywhere, I would probably continue--simply because I have no idea how to stop. But writing only for myself has never been my goal. I write to share who I am and what I know, what I've seen and heard and felt; I write to resurrect the lost and to give flesh and voice to the ghosts who often take up residence in my study.